Sir Hitch and Uncle Walt: Feud? What Feud?

AS THE HISTORY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY CINEMA is sifted down by the passage of years, the list of remembered names of pioneering filmmakers will, sadly, grow shorter. Already today, names like Méliès, Griffith, Chaplin and DeMille are being eclipsed by those of Spielberg, Kubrick, Scorsese and, god help us, Tarantino. But if you’re placing bets on the ones who’ll still be remembered and studied centuries from now, the odds are high for two household names: Walt Disney and Alfred Hitchcock.

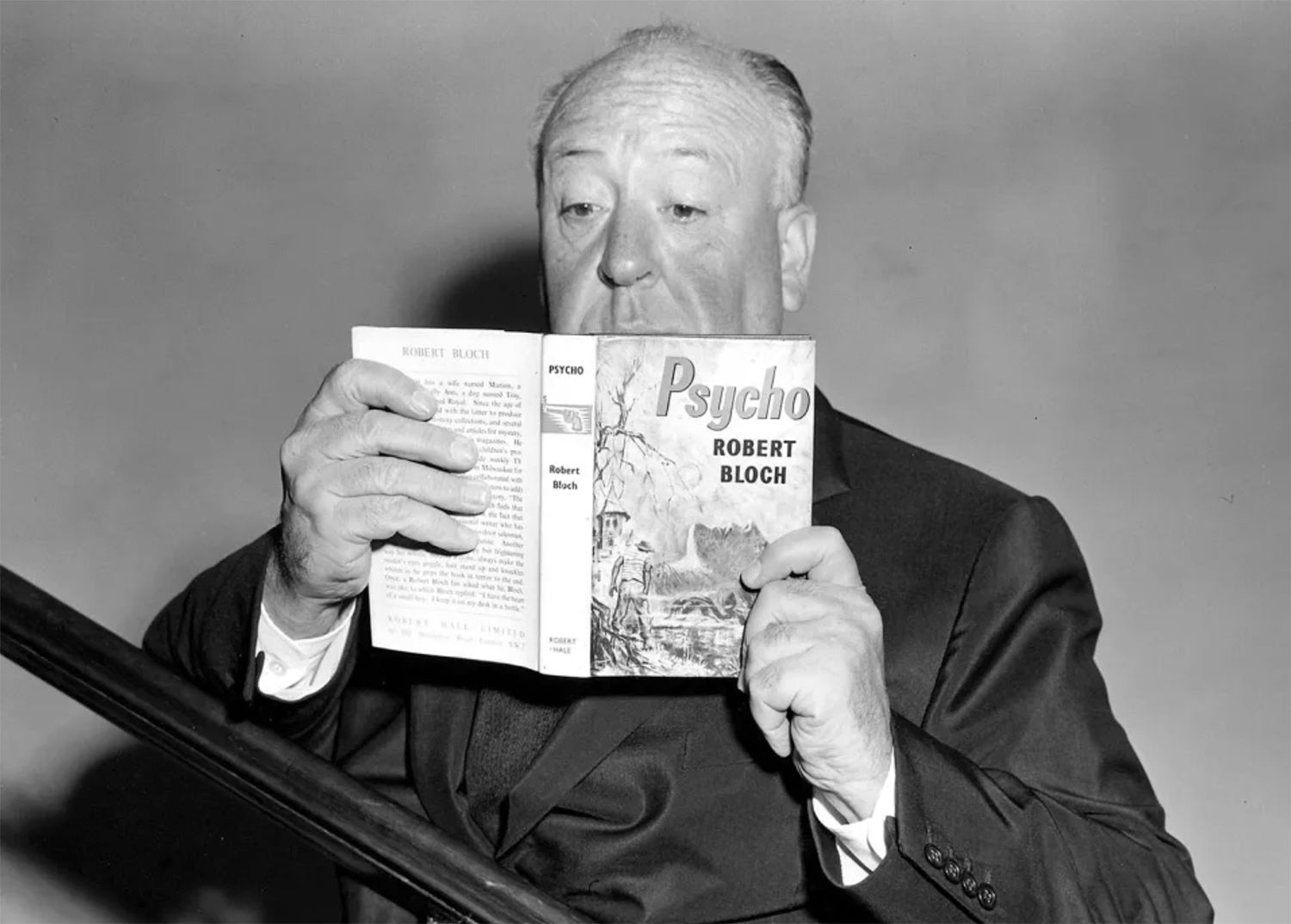

The echo chamber that is the internet is doing its part to keep their memory alive. There, you can easily find two endlessly repeated anecdotes that purport to describe how they regarded each other. One is a famous Hitchcock quote: “I've always said that Walt Disney has the right idea. His actors are made of paper; when he doesn't like them, he can tear them up." The other concerns Disney himself, who, after seeing Psycho—a “disgusting” film he would never let his children go to—refused to let Hitchcock shoot a film in Disneyland. Walt’s declaration has been exaggerated over the decades, resulting in wild assumptions that Hitchcock himself was forever banished from The Happiest Place On Earth, or that there was a long lasting Disney-Hitchcock feud. Is there any truth to these stories?

Hitchcock’s comment was an addendum to a much more famous quote early in his career, that actors should be treated like cattle—a startling motto that he delighted in repeating. Meanwhile, Walt’s rather severe remark may have been less about Hitchcock personally than it was a promoter’s defense of the park’s wholesome family image. Fair enough. But is there any reason to think that these two wouldn’t have recognized and respected each other’s genius? It was certainly true of Hitchcock, who was known to be a Disney admirer for all his professional life.

It can be argued that drawn animation is the purest form of pure cinema. It not only creates an emotional response from successive images, it also creates the images. But Hitchcock’s use of cell animation was sparse and rare. Scottie’s nightmare in Vertigo startles the viewer with a few seconds of animated flower petals bursting apart. In The Birds, animation is hiding in plain sight, when rotoscoped seagulls are combined with the overhead view of Bodega Bay’s fiery disaster. But that’s it! Fans worldwide may always wonder what might have been the result of a fully animated Hitchcock film—especially a collaboration with Disney. It almost happened. In the 1940s, Walt briefly considered animating an Edgar Allen Poe story (proposed by actor James Mason) and asking Hitch to direct. But what we do have are some indirect collaborations between them—and some remarkable parallels.

Walter Elias Disney was two years younger than Alfred Joseph Hitchcock, but they started their careers in the film industry at about the same time. Both had made their living from a drawing board before putting their talent to films. Young Alfred entered the British film industry as a title designer in 1919, and quickly climbed the ladder by making sure he pleased each man he worked for. Young Walter, disinclined to work for others, became his own boss in 1923, when he set up what would become The Walt Disney Company, partnering with his brother Roy and his best friend, artist Ub Iwerks. By 1927, Hitchcock had established himself as England’s most promising director, while, across the pond, in 1928, Disney and Iwerks created Mickey Mouse. History continues to debate who was the more creatively and artistically responsible. Their little mouse debuted in the first successful sound cartoon Steamboat Willie, making instant stars of Mickey and Walt—and in 1929, Hitchcock was heralded for making Britain’s innovative first talkie, Blackmail. The film industry was rapidly maturing, and these two leaders advanced apace.

As the 1930s progressed, both knew that their brand was as important as their films. In the tradition of Dickens, Hitchcock believed that “The name of the director should be associated in the public’s mind with a quality product.” To that end, he would employ a publicist as early as 1930. Disney, fiercely defending the copyright of Mickey Mouse until the end of the world, also made sure that each cartoon told the audience they were seeing “A Walt Disney Production,” effectively taking the first, and sometimes only, bow. Hitchcock, some years away from seeing his name being above the title, peeked at the audience from behind the curtain by way of his charming and strategic cameo appearances.

Dis and Hitch were the first auteurs widely known to use the storyboarding process. Disney would storyboard the entirety of his animated films—a necessary guide for an army of animators. Perhaps Hitchcock took a cue from Walt: he would also micromanage his films this way—or, at least, he wanted us to think so. While storyboarding was organic to the needs of animators, live action filming had more flexibility. But the intent for both men was the same: to have as much control as possible over the final product by putting their vision on paper before cameras rolled.

Hitchcock and Disney became so associated with their respective genres that to stray from them was risky, and to break their own rules, taboo. But they sometimes dared. For instance, in 1942’s Bambi, a story about life and survival in the forest from the point of view of its wildlife, Disney went for a more dramatic and realistic treatment, perhaps somewhat closer to Hitchcock’s style. Mid-film, after starving through a bitter winter, adorable fawn Bambi and his beloved mother are finally finding food to graze upon, when Disney plays a dirty trick. The mother is shot and killed—mercifully offscreen—by an unseen human hunter. Bambi cries in terrified abandonment. No blue fairy or magic kiss would bring her back. “Unfair!” cried the audience, and the movie suffered at the box office.

Hitchcock had already played a similar trick in 1936’s Sabotage. Karl Verloc, his much younger wife, and her kid brother Stevie (Oscar Homolka, Sylvia Sidney and Desmond Tester, respectively) live in a modest dwelling behind the neighborhood movie theater they run. But kindly-seeming Verloc is actually a member of a shadowy terrorist ring, secretly performing acts of sabotage around London. Mid-film, Verloc, knowing he is being watched, sends little Stevie on an errand across town with a package into which he’s secreted a cache of timed explosives to leave in a cloakroom, telling him it must get there before 1:45. Unaware of the danger he’s in, Stevie is delayed by several simple distractions, and is aboard a public bus stuck in traffic as 1:45 fast approaches. The audience is at the edge of its seats in agonizing suspense. But then Hitch plays his dirty trick. The bomb goes off. The bus explodes, and the little boy is killed. (Along with a little dog for good measure.) “Unfair!” cried the audience, and the movie suffered at the box office.

It was this film that brought about their first and most significant indirect collaboration, when Disney granted permission for Hitchcock to use a scene from one of his cartoons. The Silly Symphony short Who Killed Cock Robin? starring “bird-icatures” of Bing Crosby and Mae West contains a comedic scene of the titular bird being shot down by an unseen assailant. Being a Disney cartoon, it ends happily in the revelation that the resurrected Cock Robin was never really dead, the arrow having come only from a cupid bird.

This cartoon is playing in her theater when Mrs. Verloc, still in shock from the loss of her brother, is momentarily comforted by the film and the children’s laughter. But Hitchcock uses only the cartoon’s murder scene, altering the soundtrack to make it more sinister, and twisting the carving knife in Mrs. Verloc’s grieving heart as she watches Cock Robin spiral to an ugly death.

Why would Disney let his cute Technicolor characters be misused this way? Well, the indignant Mr. Disney of 1960 might have refused to accommodate Hitchcock, but not the young Walt of 1936, who surely welcomed the generated revenue and publicity, as his studio struggled to finance his folly, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first full length animated feature. Released the following year, that 83-minute cartoon was a smash and changed cinema forever. More fantastic Disney films followed in 1940, the year that Hitchcock triumphed with his first American film, Rebecca. Hitch and Walt were now among the most successful and recognized non-actors in Hollywood. But a big bad wolf was on its way.

As war had approached in Europe, Hitchcock’s classic The Lady Vanishes was a disguised cautionary tale for 1938 British audiences. In 1940, his U.S. thriller Foreign Correspondent ended with a blatant warning to still-complacent Americans. But because Hitchcock did not immediately return to defend England, his patriotism was unfairly called into question by some he’d left behind in his mother country. Disney’s patriotism held no such ambiguity. His all-American background was unquestioned, and his new Burbank studio was completely assigned to the war effort directly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Walt went into personal debt financing his unique adaptation of the bestseller Victory Through Air Power. Completed in 1943, the animated documentary was said to have influenced strategic decisions by Roosevelt and Churchill. But while it was received enthusiastically by servicemen and critics, the film was only given limited release in local theaters.

In 1942, American audiences welcomed Hitchcock's entertaining and patriotic Saboteur. But his more direct war work was indeed done back home in the United Kingdom, with two French resistance propaganda shorts, some uncredited scene direction in a patriotic British film and his work as an advisor on a documentary chronicling the shocking torture of the concentration camps. With its disturbing footage, ironically, the latter wasn’t shown publicly until the 1980s. Walt continued to boost morale for the public and the troops with patriotic Donald Duck shorts, complete with the standard caricatures of Germans and Japanese. Hitch’s final American statement during the war would come in his largely misunderstood parable Lifeboat, in which the emphasis is on civilians in moments of desperation, with the war itself as the MacGuffin.

No matter how righteous or necessary, no matter who supports and who resists, war’s price tag on humanity is always high. So, who set a better example for future generations in a time of crisis, and is that even right to ask? Walt showed us who to fight, and how. Hitch showed us who to help, and what to hope for. Both of our legends dutifully and generously gave of their time and talents, publicly and privately, to support the Allies. After peace was declared, Hitchcock would continue to showcase the human toll of the cold war, and Walt went back to the business of creating beautifully realized escapist family entertainment, on and beyond the screen. Since nearly all of Hitchcock’s war-related features have never been out of public view, and Disney’s are now little known and mostly relegated to the legendary “Walt Vault,” perhaps it isn’t fair to make comparisons. Or perhaps that simply is the comparison.

After the war, there were more parallels. Both men would dial D for Dalí, when the acclaimed Spanish painter came to take on Hollywood. But Walt would get the sloppy seconds. First, Hitchcock signed Dalí to create surrealistic designs for the dream sequence in his 1945 hit Spellbound. Then, Disney contracted Salvador to work on a six-minute episode of a planned film called Destino, but it was left unfinished – until the year 2003, when it was finally completed.

In the mid-1950s, Hitchcock and Disney each began hosting weekly anthology programs on television, using the carefully-crafted alter-ego personas they had been presenting to their public. Millions of people came to memorize Disney’s flourishing signature and Hitchcock’s simply drawn self-caricature. And they both earned a lot of money. Hitchcock was still focused primarily on his day job of making great motion pictures, but made time to introduce every episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and to direct some of them himself. Disney used his television programs first to publicize his newest folly, Disneyland, then began mining his archives and branching out with more shows, far outlasting Hitchcock’s ten-year television run.

With his 1959 film Sleeping Beauty, Walt tried to lure his TV viewers back to the theater to see a new style of animation, in a brand new format, Super Technirama 70 widescreen. Now regarded as one of the studio’s greatest achievements, the film failed on its release; it made a profit, but too mild to match the astounding production costs. Uncle Walt had to lay off most of his animation department. Shortly after, Hitchcock took the biggest gamble of his own career. He self-financed a low-budget black and white thriller which, technically, boasted little more than what his audience would get on television, besides a bigger picture and an evening out. He launched his famous interactive marketing gimmick for Psycho, deploying his droll television persona to instruct his audience to keep its ending to themselves. Now it was Hitch who changed cinema forever. Despite misappreciation from the critics, the theaters were packed. His investment return was immense.

Next, Hitchcock reunited with Ernest Lehman, his screenwriter from North By Northwest. Ernie told Hitch about his idea for a new thriller. The story was about a blind man who sees for the first time when he receives a transplant of a donated pair of eyes, and while enjoying himself in Disneyland, somehow recognizes a man he could never have seen before. It would turn out that the stranger is the man who had murdered the previous owner of the eyes. They had begun developing a script entitled Blind Man when word came that Walt Disney learned of their plans and, reportedly, stated publicly that Hitchcock and his crew were Banned from the Land.

Or did he?

An actual quote or statement by Walt Disney from a press release or newspaper article may be lost to history, if one ever existed. Most of the story can be traced back to Ernie Lehman’s recounting, which would mutate over the years. The Gospels according to Taylor, Spoto, and McGilligan vary on whether Walt really saw Psycho, whether he indeed called the film “disgusting,” and whether he proclaimed that he would never let his children see it. (Incidentally, Walt’s two children at that time were aged 25 and 28.) Was the description of Disney’s reaction exaggerated—and if so, by Lehman, Hitch, Disney, or “telephone?” Was Lehman bitter? Walt’s refusal had led him to abandon the script, causing a rift with Hitch.

Whatever the truth, it didn’t seem to matter two years later, when Hitchcock was making his actual follow-up to Psycho. For The Birds, Disney agreed to let Hitch use his studio’s optical effects team under the personal supervision of Ub Iwerks. Iwerks had himself survived a bitter rift with Disney, back in the 30s when Ub, the co-creator and chief animator of Mickey Mouse, walked out on Disney due to a better offer, leaving behind poor working conditions, low pay, and worst of all, lack of acknowledgement. Walt was shocked and deeply hurt, and his stories about the creation of Mickey would begin to minimize Iwerks’ contribution. But Ub returned to the studio in 1940, to create the Disney Photo Effects Lab, making it the envy of Hollywood. By 1962, he had advanced the optical combining of foreground and background with his perfected yellow sodium vapor process, an improvement over bluescreen and its halo effect. With Walt’s blessing, The Birds was able to boast the most sophisticated special effects of its time, just as Mary Poppins would the year after – which, by the way, won an Oscar for Ub.

Before The Birds was finished, Walt had written to Hitch suggesting his newest star, Susan Hampshire, for the title part of Hitchcock’s next film, Marnie. Of course, that didn’t happen, yet when the film was in production, and Hitch was considering using a mechanical horse for some of the shots in the fox hunt scene, he sent his assistant director, Hilton A. Green, to see the one Disney had. As Green watched a demonstration of the phony horse at the Burbank studio, Mr. Disney came up behind him. Green recalled: “He knew that I was there for Mr. Hitchcock, and he was very interested. He admired Mr. Hitchcock deeply, and he wanted this to work... because he wanted to help Mr. H. in whatever way he could.”

Walt lost his life in 1966, just as one of his greatest discoveries, Julie Andrews, was baring her shoulders in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain. Reportedly, Hitch always kept up with Disney releases from his private screening room, even toward the end of his own life in 1980. Their names and legends will unquestionably last for centuries, but in the nearer future, let’s hope that the “feud” will end.